How Docker works

Lots of people don’t know what is behind Docker, and for many of them it’s not even something necessary to grasp, but I believe understanding the underpinning make things more transparent.

In order to understand how Docker works, we must go through some foundational concepts, and these concepts are the bones of Docker. So, let’s get started 🙂

Prerequisites

Because it’s an advanced topic, I assume you know the basic of Docker, something like running and stopping containers would be enough.

You must to install Docker on a Linux machine, I use VMWare fusion (virtual machine program for macOS) for this purpose, but you can use any platform.

There are two reasons why I’m insisting on Linux to run Docker:

- I’m not a Windows user 😀

- Docker runs as a lightweight virtual machine on macOS, so it has nothing to do with processes! As we’ll see the processes are the bones of Docker.

Do not use Docker on production for macOS, you may only use it for testing or any other use cases except production.

Docker vs VMs

One of the frequently asked questions is what the difference between Docker and VMs is?

Well, I can answer this question by saying:

Docker relies on Linux namespaces and control groups whereas VM relies on Hypervisor.

I reckon this answer still ambiguous.

So, let’s move on and explain what Linux processes are.

Linux Processes

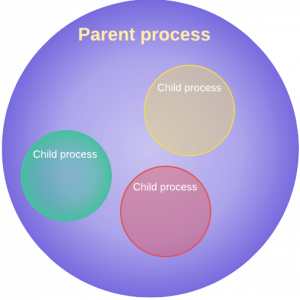

n Linux, the process is an instance of a running (executing) program, and each process assigned a PID (process ID) by the system.

In addition to the PID, each process is a child of a parent process (PPID), and the mother of all the processes is init process.

We can view the running processes tree by using the ps as follows:

ps axjf

Another way to view the process tree is by running

pstreecommand without any options.

The ps (process status) command is one of the most used commands on Linux, it's used to provide information about the currently running processes.

If you want to view all the running processes then you could use the ps as follows:

ps aux

Let's demystify the given arguments:

-

ameans all the processes. -

ushows detailed information about each process. -

xmeans also show the none-associated terminal processes e.g daemons.

I guess that

auxare the most used options for thepscommand.

Each process gets its own folder with its relevant files (configurations, root directory, security settings, etc…), all these files are saved under /proc/PROCESS_ID and can be easily viewed just like other directories/files.

Does it mean we could modify the container files/directories from /proc directory? Yes we can! As I mentioned earlier, the container is just a normal Linux process with some condiments 🤪.

We’ll get into

/procsoon.

Virtual Machines

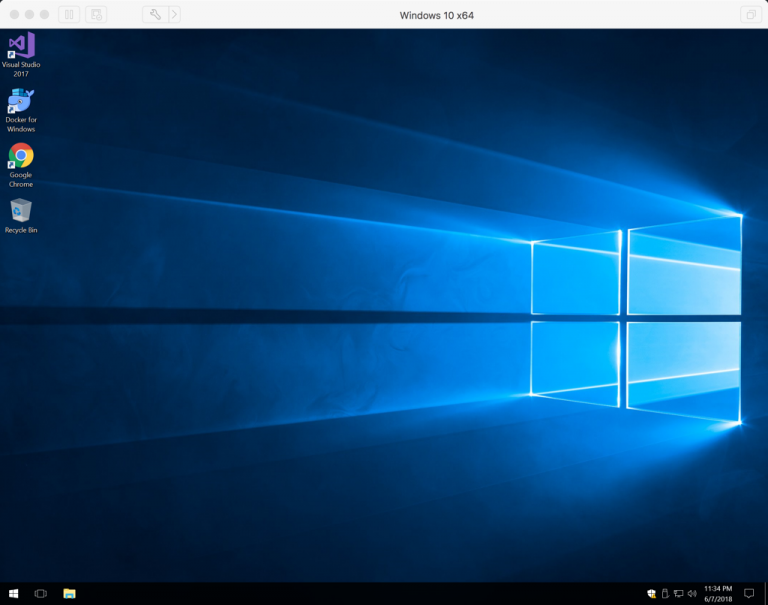

VM or Virtual Machine is just a software we install on our physical computer to run an operating system and applications, for example, here I’m running Windows 10 inside my MacBook Pro by using VMWare fusion:

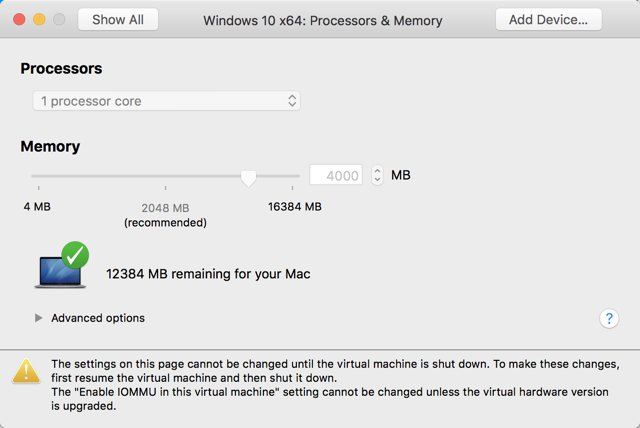

The VM is a slice of a physical computer (hardware) with limited resources (CPU, RAM, Storage, etc…), and it looks like as if it’s an independent machine.

Let’s examine that by taking a look at the Windows 10 VM settings, as you can see this VM has only one processor core assigned and almost 4GB of RAM:

Windows 10 has no idea about other hardware resources on the host machine, it’s only knows about whatever we assign to it, which in this case one core processor and 4 GB of RAM.

But, how does the this magic (virtualization) works? Well, it’s all about Hypervisor.

Hypervisor or Virtual Machine Monitor (VMM) is a piece of software to create virtualized environments, these environments will be entirely separated from the host machine, and also from each other.

There are two types of Hypervisor:

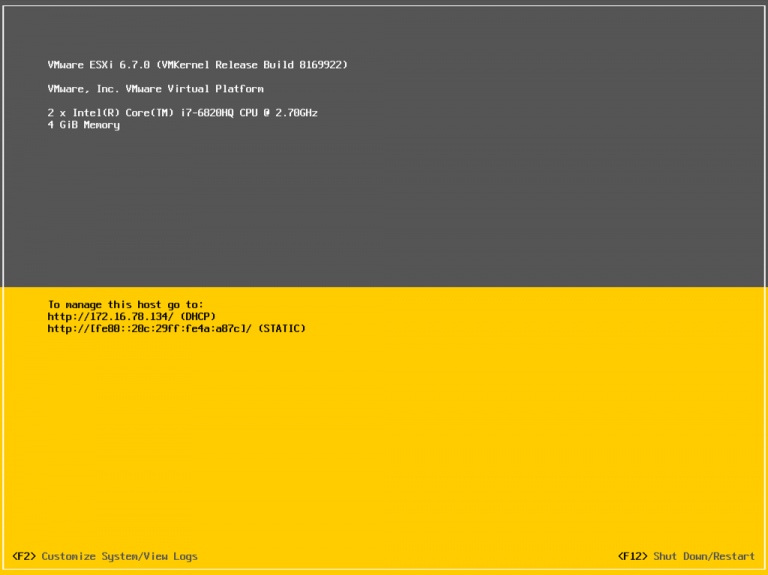

Type 1: mostly used for servers, the software for this type will be directly installed on the hardware, just like installing an operating system from a bootable device (USB, DVD, etc…), the most used softwares for this type are:

- VMware ESXi: I call it the King 😀

- Hyper-V: from Microsoft.

- KVM: from Linux world.

The following screenshot shows a Vmware ESXi instance that is directly installed on a physical machine:

Type 2: In this type, the software will be installed on the operating system level, for example we can run Windows 10 inside Mac or vise versa (Figure 2), the most used applications for this type are:

- VirtualBox: cross platform.

- Vmware fusion: only for Mac

- Parallels: only for Mac.

- VMware Workstation: only for Windows.

So, enough theory! 😀 Let’s dive into containers and see what they really are.

Containers

The container is a Linux kernel feature which allows us to isolate processes.

In straightforward words, the container is just a Linux process running in a sandboxed way.

Imagine you have multiple processes running on your computer, and you create another isolated process (container), the isolated process will not be able to see the host processes, it does not even know they exist! So, it’s entirely separated from the host and other containers.

Let’s demystify this by running a memcached container:

docker run --name memcached -d memcached

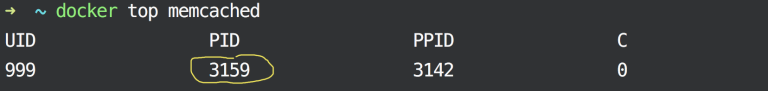

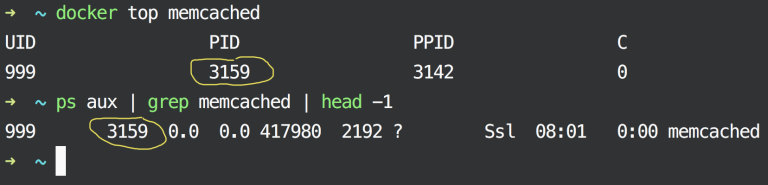

We ran a memcached container in the background, let’s examine the running processes for it:

docker top memcached

Let's see the output:

Please bear in mind that the

docker topcommand is used to list the running processes inside the container NOT the host.

As you can see, there’s only one process running inside the Memcached container! It means that the Memcached container is utterly isolated from the host and also from other containers, in addition to that it cannot access any of the host processes.

As I mentioned earlier, Docker container is just a Linux process, so let’s prove it by running the following command on our host machine:

ps aux | grep memcached | head -1

The following output shows that the Docker container is nothing but a normal Linux process, take a look at the PID, both are the same:

See, it’s just a normal Linux process named memcached running on our host machine.

Again, Docker container is just a normal Linux process, just keep it in mind 🙂

Time to get into /proc directory and see how we could modify the container’ contents without using Docker.

As I mentioned earlier, each Linux process gets its own directory inside /proc.

The /proc directory is a virtual file system contains the processes information.

Start by creating a file inside the Memcached process root directory and then read this file from the host, so first, we need to get the PID of the Memcached container as follows:

MEM_PID=$(pgrep memcached)

cd /proc/$MEM_PID

Then just create an empty file inside container’s root directory:

cd root/

touch created_by_${HOST}

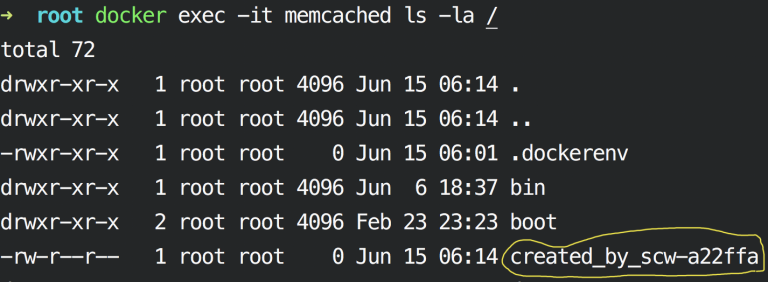

List the filesytem / folder inside the Memcached container:

docker exec -it memcached ls /

As you can see here, any changed we make in /proc will be reflected inside the container, because (and again) the container is just a regular Linux process.

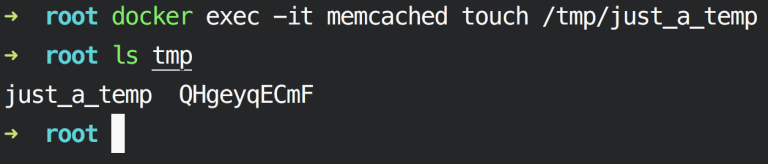

Now, let’s do the flip side, create a file inside the container and view it on the on the host:

docker exec -it memcached touch /tmp/just_a_temp

ls tmp

Yes, both files are accessible on both host and container.

Namespaces

Docker relies on Linux namespaces to do all that magic (containerization).

Without namespaces containers won’t exist, which means no Docker! but why? It’s because of isolation!

Imaging you have PHP and Postgres processes up and running, without isolation these two processes can modify each other resources, for example PHP can delete Postgres data, but with namespaces, PHP doesn’t even know Postgres exist!

So, what namespaces are?

Namespaces is a Linux kernel feature which allows us to isolate the processes from each other, and limit what a process can see, so each namespaced process gets its own:

- Process ID (pid): isolate the PID number space.

- Mount (mnt): isolate filesystem mount points.

- Network (net): isolate network interfaces.

- Interprocess Communication (ipc): isolate interprocess communication (IPC) resources

- UTS: isolate hostname and domainname.

- User ID (user): isolate cgroup root directory.

Namespaces can’t limit access to physical resources such as CPU, RAM, and Storage.

We could use unshare command to create a namespace and attach the current process into it, here we’re running a bash prompt in its own namespace:

unshare --fork --pid --mount-proc bash

ps aux

exit

Since bash is running in its own namespaced area, we have to issue exit to terminate it and back to our host shell.

Control groups

Control groups (aka cgroups) limit the access to physical resources such as CPU, RAM and Storage.

Unlike namespaces, the cgroup is just a plain text file located under /proc/PROCESS_ID/cgroup:

cat /proc/$MEM_PID/cgroup

If you take a look at the second column (colon separated) you can see some names like (pids, cpu, cpuacct, net_cls etc…) these are physical folders on the disk, and they are located under /sys/fs/cgroup/.

Each Docker container saves its cgroup configuration in /sys/fs/cgroup/CGROUP_TYPE/docker/CONTAINER_ID:

#Memory configuration for Memcached

#Please change 1b1... to the Memcached container ID

ls -l /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/docker/1b15587a72eb8d4d3343c78f8140c695dc1af4151103729049dcab4329f2c46e

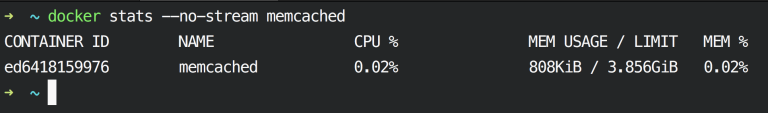

Imagine you want to allocate 1 GB of the RAM, instead of 4 GB, so, first of all, let’s see how much available memory assigned to Memcached:

Modify the memory limit as follows:

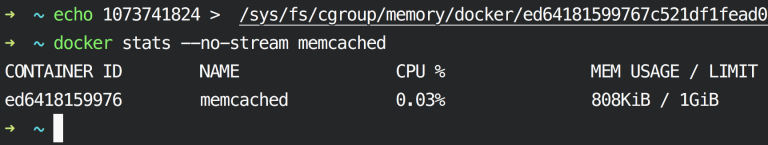

echo 1073741824 > /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/docker/MEMCACHED_CONTAINER_ID/memory.limit_in_bytes

Check if the memory limit is changed by issuing the stats command again:

docker stats --no-stream memcached

So, now the Memcached container has 1 GB of RAM.

IMPORTANT: Do not modify cgroups files or any Docker configuration files on production. Instead of modifying crazy cgroups to limit container resources, you could use Docker built in limit a container’s resources.

Conclusion

Linux namespaces and cgroups are the bones of Docker, we saw how we could use these two features to isolate the process and limit the resources.

We also saw how the Docker container behaves when we change the namespace contents.